Tag / Resurrection of Jesus

Jesus the Cold Case: Mark Keown Responds to the documentary by Bryan Bruce

“Through the program Bryan Bruce drew on a range of scholars like NZ’s own Lloyd Gering, Bishop Spong, Dominic Crossan and others. Without exception, the scholars drawn on are a particular breed of liberals (e.g. Jesus Seminar) with a particular viewpoint and agenda i.e. they reject the Scriptures and revision them radically reinterpreting Christianity through a liberal skeptical lens. They pick and choose which bits of the Bible they prefer, rejecting others. Now, unbeknown to Bruce and many others, there are a vast array of biblical scholars and theologians out there who find their views incorrect at many levels. Some names that did not feature in this are N.T. Wright, Ben Witherington, Craig Blomberg, Don Carson and Richard Bauckham, among many others. Most if not all the things discussed in the program have been discussed in biblical scholarship. Through the program we hear ‘most/some/all biblical scholars’ again and again – let the reader know, his confidence is misplaced and arrogant. He does not have any idea what ‘most, some and all’ biblical scholars think, he has not done his homework. It is absolutely unacceptable to present such a biased perspective when there is mountains of scholarship that can be brought alongside what he put together to critique it.” Mark Keown

Source: Mark Keown: Jesus the Cold Case: A Response

Carl Jung on Accepting the Darkness of Self and Others – YouTube

The Real Face of Jesus from the Shroud of Turin

“Changing Your Spiritual Lens” – Part 2 By Graham Cooke

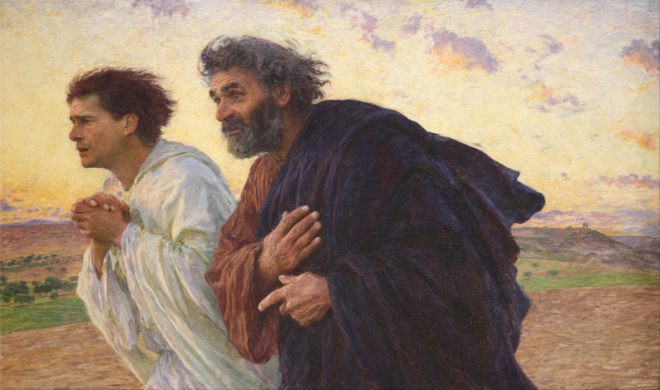

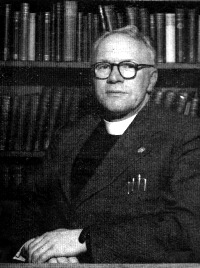

The Resurrection and the Life– by William Barclay

The Resurrection and the Life (Jn 11:20-27)

11:20-27 So when Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went to meet him, but Mary remained sitting in the house. So Martha said to Jesus: “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. And even as things are, I know that whatever you ask God, God will give you.” Jesus said to her: “Your brother will rise again.” Martha said to him: “I know that he will rise at the resurrection on the last day.” Jesus said to her: “I am the Resurrection and the Life. He who believes in me will live even if he has died; and everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him; “Yes, Lord. I am convinced that you are God’s Anointed One, the Son of God, the One who is to come into the world.”

In this story, too, Martha is true to character. When Luke tells us about Martha and Mary (Lk 10:38-42), he shows us Martha as the one who loved action, and Mary as the one whose instinct was to sit still. It is so here. As soon as it was announced that Jesus was coming near, Martha was up to meet him, for she could not sit still, but Mary lingered behind.

When Martha met Jesus her heart spoke through her lips. Here is one of the most human speeches in all the Bible, for Martha spoke, half with a reproach that she could not keep back, and half with a faith that nothing could shake. “If you had been here.” she said, “my brother would not have died.” Through the words we read her mind. Martha would have liked to say: “When you got our message, why didn’t you come at once? And now you have left it too late.” No sooner are the words out than there follow the words of faith, faith which defied the facts and defied experience: “Even yet,” she said with a kind of desperate hope, “even yet, I know that God will give you whatever you ask.”

Jesus said “Your brother will rise again.” Martha answered: “I know quite well that he will rise in the general resurrection on the last day.” Now that is a notable saying. One of the strangest things in scripture is the fact that the saints of the Old Testament had practically no belief in any real life after death. In the early days, the Hebrews believed that the soul of every man, good and bad alike, went to Sheol. Sheol is wrongly translated Hell; for it was not a place of torture, it was the land of the shades. All alike went there and they lived a vague, shadowy, strengthless, joyless ghostly kind of life. This is the belief of by far the greater part of the Old Testament. “In death there is no remembrance of thee: in Sheol who can give thee praise?” (Ps 6:5). “What profit is there in my death if I go down to the pit? Will the dust praise thee? Will it tell of thy faithfulness?” (Ps 30:9). The Psalmist speaks of “the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom thou dost remember no more; for they are cut off from thy hand” (Ps 88:5). “Is thy steadfast love declared in the grave,” he asks, “or thy faithfulness in Abaddon? Are thy wonders known in the darkness, or thy saving help in the land of forgetfulness?” (Ps 88:10-12). “The dead do not praise the Lord, nor do any that go down into silence” (Ps 115:17). The preacher says grimly: “Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with your might; for there is no work or thought or knowledge or wisdom in Sheol, to which you are going” (Ecc 9:10). It is Hezekiah’s pessimistic belief that: “For Sheol cannot thank thee, death cannot praise thee; those who go down to the pit cannot hope for thy faithfulness” (Isa 38:18). After death came the land of silence and of forgetfulness, where the shades of men were separated alike from men and from God. As J. E. McFadyen wrote: “There are few more wonderful things than this in the long history of religion, that for centuries men lived the noblest lives, doing their duties and bearing their sorrows, without hope of future reward.”

Just very occasionally someone in the Old Testament made a venturesome leap of faith. The Psalmist cries: “My body also dwells secure. For thou dost not give me up to Sheol, or let thy godly one see the pit. Thou dost show me the path of life; in thy presence there is fullness of joy, in thy right hand are pleasures for evermore” (Ps 16:9-11). “I am continually with thee; thou dost hold my right hand. Thou dost guide the with thy counsel, and afterward thou wilt receive me to glory” (Ps 73:23-24). The Psalmist was convinced that when a man entered into a real relationship with God, not even death could break it. But at that stage it was a desperate leap of faith rather than a settled conviction. Finally in the Old Testament there is the immortal hope we find in Job. In face of all his disasters Job cried out:

“I know that there liveth a champion,

Who will one day stand over my dust;

Yea, another shall rise as my witness,

And, as sponsor, shall I behold—God;

Whom mine eyes shall behold, and no stranger’s.”

(Job 14:7-12; translated by J. E. McFadyen).

Here in Job we have the real seed of the Jewish belief in immortality.

The Jewish history was a history of disasters, of captivity, slavery and defeat. Yet the Jewish people had the utterly unshakable conviction that they were God’s own people. This earth had never shown it and never would; inevitably, therefore, they called in the new world to redress the inadequacies of the old. They came to see that if God’s design was ever fully to be worked out, if his justice was ever completely to be fulfilled, if his love was ever finally to be satisfied, another world and another life were necessary. As Galloway (quoted by McFadyen) put it: “The enigmas of life become at least less baffling, when we come to rest in the thought that this is not the last act of the human drama.” It was precisely that feeling that led the Hebrews to a conviction that there was a life to come.

It is true that in the days of Jesus the Sadducees still refused to believe in any life after death. But the Pharisees and the great majority of the Jews did. They said that in the moment of death the two worlds of time and of eternity met and kissed. They said that those who died beheld God, and they refused to call them the dead but called them the living. When Martha answered Jesus as she did she bore witness to the highest reach of her nation’s faith.

Barclay’s Daily Study Bible (NT).

Risk of Preaching on Genesis–Joel Hunter

The Lost Tomb of Jesus – James Cameron – Habermas Response

12 Major Problems for the “Jesus Tomb” Theory

12 Major Problems for the “Jesus Tomb” Theory

via The Lost Tomb of Jesus – James Cameron – Habermas Response.

Holy War–Greg Boyd