Category / Theology

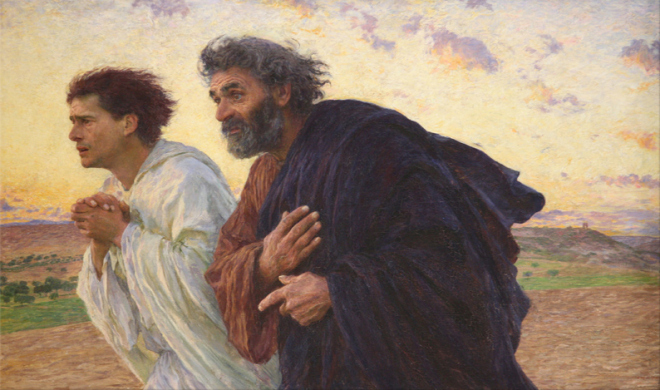

The Story of the Loving Father—William Barclay

Parable of the Prodigal Son

(Luke 15:11-32)

Jesus said, “There was a man who had two sons. The younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the part of the estate which falls to me.’ So his father divided his living between them. Not many days after, the son realized it all and went away to a far country, and there in wanton recklessness scattered his substance. When he had spent everything a mighty famine arose throughout that country and he began to be in want. He went and attached himself to a citizen of that country, and he sent him into his fields to feed pigs; and he had a great desire to fill himself with the husks the pigs were eating; and no one gave anything to him. When he had come to himself, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have more than enough bread, and I—I am perishing here with hunger. I will get up and I will go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer fit to be called your son. Make me as one of your hired servants.”‘ So he got up and went to his father. While he was still a long way away his father saw him, and was moved to the depths of his being and ran and flung his arms round his neck and kissed him tenderly. The son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer fit to be called your son.’ But the father said to his servants, ‘Quick! Bring out the best robe and put it on him; put a ring on his finger; put shoes on his feet; and bring the fatted calf and kill it and let us eat and rejoice, for this my son was dead and has come back to life again; he was lost and has been found.’ And they began to rejoice.

“Now the elder son was in the field. When he came near the house he heard the sound of music and dancing. He called one of the slaves and asked what these things could mean? He said to him, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf because he has got him back safe and sound.’ He was enraged and refused to come in. His father went out and urged him to come in. He answered his father, ‘Look you, I have served you so many years and I never transgressed your order, and to me you never gave a kid that I might have a good time with my friends. But when this son of yours—this fellow who consumed your living with harlots—came, you killed the fatted calf for him.’ ‘Child,’ he said to him, ‘you are always with me. Everything that is mine is yours. But we had to rejoice and be glad, for your brother was dead and has come back to life again; he was lost and has been found.'”**

Not without reason this has been called the greatest short story in the world. Under Jewish law a father was not free to leave his property as he liked. The elder son must get two-thirds and the younger one-third. (Deut 21:17.) It was by no means unusual for a father to distribute his estate before he died, if he wished to retire from the actual management of affairs. But there is a certain heartless callousness in the request of the younger son. He said in effect, “Give me now the part of the estate I will get anyway when you are dead, and let me get out of this.” The father did not argue. He knew that if the son was ever to learn he must learn the hard way; and he granted his request. Without delay the son realized his share of the property and left home.

He soon ran through the money; and he finished up feeding pigs, a task that was forbidden to a Jew because the law said, “Cursed is he who feeds swine.” Then Jesus paid sinning mankind the greatest compliment it has ever been paid. “When he came to himself,” he said. Jesus believed that so long as a man was away from God he was not truly himself; he was only truly himself when he was on the way home. Beyond a doubt Jesus did not believe in total depravity. He never believed that you could glorify God by blackguarding man; he believed that man was never essentially himself until he came home to God.

So the son decided to come home and plead to be taken back not as a son but in the lowest rank of slaves, the hired servants, the men who were only day labourers. The ordinary slave was in some sense a member of the family, but the hired servant could be dismissed at a day’s notice. He was not one of the family at all. He came home; and, according to the best Greek text, his father never gave him the chance to ask to be a servant. He broke in before that. The robe stands for honour; the ring for authority, for if a man gave to another his signet ring it was the same as giving him the power of attorney; the shoes for a son as opposed to a slave, for children of the family were shod and slaves were not. (The slave’s dream in the negro spiritual is of the time when “all God’s chillun got shoes,” for shoes were the sign of freedom.) And a feast was made that all might rejoice at the wanderer’s return.

Let us stop there and see the truth so far in this parable.

(i) It should never have been called the parable of the Prodigal Son, for the son is not the hero. It should be called the parable of the Loving Father, for it tells us rather about a father’s love than a son’s sin.

(ii) It tells us much about the forgiveness of God. The father must have been waiting and watching for the son to come home, for he saw him a long way off. When he came, he forgave him with no recriminations. There is a way of forgiving, when forgiveness is conferred as a favour. It is even worse, when someone is forgiven, but always by hint and by word and by threat his sin is held over him.

Once Lincoln was asked how he was going to treat the rebellious southerners when they had finally been defeated and had returned to the Union of the United States. The questioner expected that Lincoln would take a dire vengeance, but he answered, “I will treat them as if they had never been away.”

It is the wonder of the love of God that he treats us like that.

That is not the end of the story. There enters the elder brother who was actually sorry that his brother had come home. He stands for the self-righteous Pharisees who would rather see a sinner destroyed than saved. Certain things stand out about him.

(i) His attitude shows that his years of obedience to his father had been years of grim duty and not of loving service.

(ii) His attitude is one of utter lack of sympathy. He refers to the prodigal, not as any brother, but as your son. He was the kind of self-righteous character who would cheerfully have kicked a man farther into the gutter when he was already down.

(iii) He had a peculiarly nasty mind. There is no mention of harlots until he mentions them. He, no doubt, suspected his brother of the sins he himself would have liked to commit.

Once again we have the amazing truth that it is easier to confess to God than it is to many a man; that God is more merciful in his judgments than many an orthodox man; that the love of God is far broader than the love of man; and that God can forgive when men refuse to forgive. In face of a love like that we cannot be other than lost in wonder, love and praise.

The Gospel of Luke, Barclay’s Daily Study Bible (NT).

** William Barclay’s translation.

Parable of the Good Samaritan—William Barclay

Who Is My Neighbour? (Luke 10:25-37)

10:25-37 Look you—an expert in the law stood up and asked Jesus a test question. “Teacher,” he said, “What is it I am to do to become the possessor of eternal life?” He said to him, “What stands written in the law? How do you read?” He answered, “You must love the Lord your God with your whole heart, and with your whole mind, and your neighbour as yourself.” “Your answer is correct,” said Jesus. But he, wishing to put himself in the right, said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbour?” Jesus answered, “There was a man who went down from Jerusalem to Jericho. He fell amongst brigands who stripped him and laid blows upon him, and went away and left him half-dead. Now, by chance, a priest came down by that road. He looked at him and passed by on the other side. In the same way when a Levite came to the place he looked at him and passed by on the other side. A Samaritan who was on the road came to where he was. He looked at him and was moved to the depths of his being with pity. So he came up to him and bound up his wounds, pouring in wine and oil; and he put him on his own beast and brought him to an inn and cared for him. On the next day he put down 10p and gave it to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and whatever more you are out of pocket, when I come back this way, I’ll square up with you in full.’ Which of these three, do you think, was neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of brigands?” He said, “He who showed mercy on him.” “Go,” said Jesus to him, “and do likewise.”**

First, let us look at the scene of this story. The road from Jerusalem to Jericho was a notoriously dangerous road. Jerusalem is 2,300 feet above sea-level; the Dead Sea, near which Jericho stood, is 1,300 feet below sea-level. So then, in somewhat less than 20 miles, this road dropped 3,600 feet. It was a road of narrow, rocky deifies, and of sudden turnings which made it the happy hunting-ground of brigands. In the fifth century Jerome tells us that it was still called “The Red, or Bloody Way.” In the 19th century it was still necessary to pay safety money to the local Sheiks before one could travel on it. As late as the early 1930’s, H. V. Morton tells us that he was warned to get home before dark, if he intended to use the road, because a certain Abu Jildah was an adept at holding up cars and robbing travellers and tourists, and escaping to the hills before the police could arrive. When Jesus told this story, he was telling about the kind of thing that was constantly happening on the Jerusalem to Jericho road.

Second, let us look at the characters.

(a) There was the traveler. He was obviously a reckless and foolhardy character. People seldom attempted the Jerusalem to Jericho road alone if they were carrying goods or valuables. Seeking safety in numbers, they traveled in convoys or caravans. This man had no one but himself to blame for the plight in which he found himself.

(b) There was the priest. He hastened past. No doubt he was remembering that he who touched a dead man was unclean for seven days (Numbers 19:11). He could not be sure but he feared that the man was dead; to touch him would mean losing his turn of duty in the Temple; and he refused to risk that. He set the claims of ceremonial above those of charity. The Temple and its liturgy meant more to him than the pain of man.

(c) There was the Levite. He seems to have gone nearer to the man before he passed on. The bandits were in the habit of using decoys. One of their number would act the part of a wounded man; and when some unsuspecting traveller stopped over him, the others would rush upon him and overpower him. The Levite was a man whose motto was, “Safety first.” He would take no risks to help anyone else.

(d) There was the Samaritan. The listeners would obviously expect that with his arrival the villain had arrived. He may not have been racially a Samaritan at all. The Jews had no dealings with the Samaritans and yet this man seems to have been a kind of commercial traveler who was a regular visitor to the inn. In John 8:48 the Jews call Jesus a Samaritan. The name was sometimes used to describe a man who was a heretic and a breaker of the ceremonial law. Perhaps this man was a Samaritan in the sense of being one whom all orthodox good people despised.

We note two things about him.

(i) His credit was good! Clearly the innkeeper was prepared to trust him. He may have been theologically unsound, but he was an honest man.

(ii) He alone was prepared to help. A heretic he may have been, but the love of God was in his heart. It is no new experience to find the orthodox more interested in dogmas than in help and to find the man the orthodox despise to be the one who loves his fellow-men. In the end we will be judged not by the creed we hold but by the life we live.

Third, let us look at the teaching of the parable. The scribe who asked this question was in earnest. Jesus asked him what was written in the law, and then said, “How do you read?” Strict orthodox Jews wore round their wrists little leather boxes called phylacteries, which contained certain passages of scripture—Ex 13:1-10; Exo 13:11-16; Deut 6:4-9; Deut 11:13-20. “You will love the Lord your God” is from Deut 6:4 and Deut 11:13. So Jesus said to the scribe, “Look at the phylactery on your own wrist and it will answer your question.” To that the scribes added Lev 19:18, which bids a man love his neighbour as himself; but with their passion for definition the Rabbis sought to define who a man’s neighbour was; and at their worst and their narrowest they confined the word neighbour to their fellow Jews. For instance, some of them said that it was illegal to help a gentile woman in her sorest time, the time of childbirth, for that would only have been to bring another gentile into the world. So then the scribe’s question, “Who is my neighbour?” was genuine.

Jesus’ answer involves three things.

(i) We must help a man even when he has brought his trouble on himself, as the traveller had done.

(ii) Any man of any nation who is in need is our neighbour. Our help must be as wide as the love of God.

(iii) The help must be practical and not consist merely in feeling sorry. No doubt the priest and the Levite felt a pang of pity for the wounded man, but they did nothing. Compassion, to be real, must issue in deeds.

What Jesus said to the scribe, he says to us—”Go you and do the same.”

Gospel of Luke, Barclay’s Daily Study Bible (NT).

** William Barclay’s translation.

Parable of the Barren Fig Tree—William Barclay

Gospel of the Other Chance and Threat of the Last Chance (Luke 13:6-9)

Jesus spoke this parable, “A man had a fig-tree planted in his vineyard. He came looking for fruit on it and did not find it. He said to the keeper of the vineyard, ‘Look you—for the last three years I have been coming and looking for fruit on this fig-tree, and I still am not finding any. Cut it down! Why should it use up the ground’ ‘Lord,’ he answered him, ‘let it be this year too, until I dig round about it and manure it, and if it bears fruit in the coming year, well and good; but if not, you will cut it down.'”**

Here is a parable at one and the same time lit by grace and close packed with warnings.

(i) The fig-tree occupied a specially favoured position. It was not unusual to see fig-trees, thorn-trees and apple-trees in vineyards. The soil was so shallow and poor that trees were grown wherever there was soil to grow them; but the fig-tree had a more than average chance; and it had not proved worthy of it. Repeatedly, directly and by implication, Jesus reminded men that they would be judged according to the opportunities they had. C. E. M. Joad once said, “We have the powers of gods and we use them like irresponsible schoolboys.” Never was a generation entrusted with so much as ours and, therefore, never was a generation so answerable to God.

(ii) The parable teaches that uselessness invites disaster. It has been claimed that the whole process of evolution in this world is to produce useful things, and that what is useful will go on from strength to strength, while what is useless will be eliminated. The most searching question we can be asked is, “Of what use were you in this world?”

(iii) Further, the parable teaches that nothing which only takes out can survive. The fig-tree was drawing strength and sustenance from the soil; and in return was producing nothing. That was precisely its sin. In the last analysis, there are two kinds of people in this world—those who take out more than they put in, and those who put in more than they take out.

In one sense we are all in debt to life. We came into it at the peril of someone else’s life; and we would never have survived without the care of those who loved us. We have inherited a Christian civilization and a freedom which we did not create. There is laid on us the duty of handing things on better than we found them.

“Die when I may,” said Abraham Lincoln, “I want it said of me that I plucked a weed and planted a flower wherever I thought a flower would grow.” Once a student was being shown bacteria under the microscope. He could actually see one generation of these microscopic living things being born and dying and another being born to take its place. He saw, as he had never seen before, how one generation succeeds another. “After what I have seen,” he said, “I pledge myself never to be a weak link.”

If we take that pledge we will fulfil the obligation of putting into life at least as much as we take out.

(iv) The parable tells us of the gospel of the second chance. A fig-tree normally takes three years to reach maturity. If it is not fruiting by that time it is not likely to fruit at all. But this fig-tree was given another chance.

It is always Jesus’ way to give a man chance after chance. Peter and Mark and Paul would all gladly have witnessed to that. God is infinitely kind to the man who falls and rises again.

(v) But the parable also makes it quite clear that there is a final chance. If we refuse chance after chance, if God’s appeal and challenge come again and again in vain, the day finally comes, not when God has shut us out, but when we by deliberate choice have shut ourselves out. God save us from that!

Gospel of Luke, Barclay’s Daily Study Bible (NT).

** William Barclay’s own translation.