William Barclay 1907-1978

From INTRODUCTION TO THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SAINT JOHN Vol.I

By William Barclay

The Beloved Disciple

… All our information about John comes from the first three gospels. It is the astonishing fact that the Fourth Gospel never mentions the apostle John from beginning to end. But it does mention two other people.

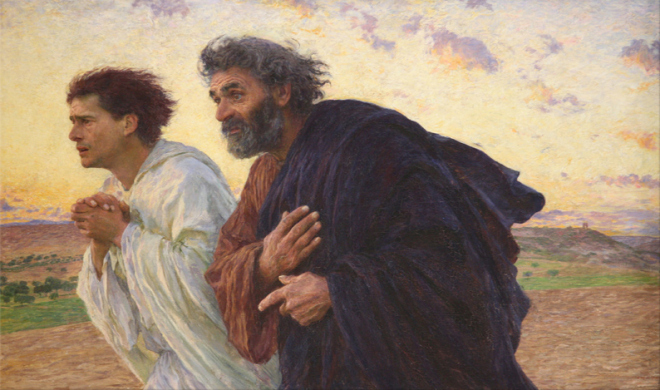

First, it speaks of the disciple whom Jesus loved. There are four mentions of him. He was leaning on Jesus’ breast at the Last Supper (John 13:23-25); it is into his care that Jesus committed Mary as he died upon his Cross (John 19:25-27); it was Peter and he whom Mary Magdalene met on her return from the empty tomb on the first Easter morning (John 20:2); he was present at the last resurrection appearance of Jesus by the lake-side (John 21:20).

Second, the Fourth Gospel has a kind of character whom we might call the witness. As the Fourth Gospel tells of the spear thrust into the side of Jesus and the issue of the water and the blood, there comes the comment: “He who saw it has borne witness–his testimony is true, and he knows that he tells the truth–that you also may believe” (John 19:35). At the end of the gospel comes the statement that it was the beloved disciple who testified of these things “and we know that his testimony is true” (John 21:24).

Here we are faced with rather a strange thing. In the Fourth Gospel John is never mentioned, but the beloved disciple is and in addition there is a witness of some kind to the whole story. It has never really been doubted in tradition that the beloved disciple is John. A few have tried to identify him with Lazarus, for Jesus is said to have loved Lazarus (John 11:3-5), or with the Rich Young Ruler, of whom it is said that Jesus, looking on him, loved him (Mark 10:21). But although the gospel never says so in so many words, tradition has always identified the beloved disciple with John, and there is no real need to doubt the identification.

But a very real point arises–suppose John himself actually did the writing of the gospel, would he really be likely to speak of himself as the disciple whom Jesus loved? Would he really be likely to pick himself out like this, and, as it were, to say: “I was his favourite; he loved me best of all”? It is surely very unlikely that John would confer such a title on himself. If it was conferred by others, it is a lovely title; if it was conferred by himself, it comes perilously near to an almost incredible self-conceit.

Is there any way then that the gospel can be John’s own eye-witness story, and yet at the same time have been actually written down by someone else?

The Production of the Church

In our search for the truth we begin by noting one of the outstanding and unique features of the Fourth Gospel. The most remarkable thing about it is the long speeches of Jesus. Often they are whole chapters long, and are entirely unlike the way in which Jesus is portrayed as speaking in the other three gospels. The Fourth Gospel, as we have seen, was written about the year A.D. 100, that is, about seventy years after the crucifixion. Is it possible after these seventy years to look on these speeches as word for word reports of what Jesus said? Or can we explain them in some way that is perhaps even greater than that? We must begin by holding in our minds the fact of the speeches and the question which they inevitably raise.

And we have something to add to that. It so happens that in the writings of the early church we have a whole series of accounts of the way in which the Fourth Gospel came to be written. The earliest is that of Irenaeus who was bishop of Lyons about A.D. 177; and Irenaeus was himself a pupil of Polycarp, who in turn had actually been a pupil of John. There is therefore a direct link between Irenaeus and John. Irenaeus writes:

“John, the disciple of the Lord, who also leant upon his breast,

himself also published the gospel in Ephesus, when he was living

in Asia.”

The suggestive thing there is that Irenaeus does not merely say that John wrote the gospel; he says that John published (exedoke) it in Ephesus. The word that Irenaeus uses makes it sound, not like the private publication of some personal memoir, but like the public issue of some almost official document.

The next account is that of Clement who was head of the great school of Alexandria about A.D. 230. He writes:

“Last of all, John perceiving that the bodily facts had been made

plain in the gospel, being urged by his friends, composed a

spiritual gospel.”

The important thing here is the phrase being urged by his friends. It begins to become clear that the Fourth Gospel is far more than one man’s personal production and that there is a group, a community, a church behind it. On the same lines, a tenth-century manuscript called the Codex Toletanus, which prefaces the New Testament books with short descriptions, prefaces the Fourth Gospel thus:

“The apostle John, whom the Lord Jesus loved most, last of all

wrote this gospel, at the request of the bishops of Asia, against

Cerinthus and other heretics.”

Again we have the idea that behind the Fourth Gospel there is the authority of a group and of a church.

We now turn to a very important document, known as the Muratorian Canon. It is so called after a scholar Muratori who discovered it. It is the first list of New Testament books which the church ever issued and was compiled in Rome about A.D. 170. Not only does it list the New Testament books, it also gives short accounts of the origin and nature and contents of each of them. Its account of the way in which the Fourth Gospel came to be written is extremely important and illuminating.

“At the request of his fellow-disciples and of his bishops, John,

one of the disciples, said: ‘Fast with me for three days from

this time and whatsoever shall be revealed to each of us, whether it be favourable to my writing or not, let us relate it to one another.’ On the same night it was revealed to Andrew that John should relate all things, aided by the revision of all.”

We cannot accept all that statement, because it is not possible that Andrew, the apostle, was in Ephesus in A.D. 100; but the point is that it is stated as clearly as possible that, while the authority and the mind and the memory behind the Fourth Gospel are that of John, it is clearly and definitely the product, not of one man, but of a group and a community.

Now we can see something of what happened. About the year A.D. 100 there was a group of men in Ephesus whose leader was John. They revered him as a saint and they loved him as a father. He must have been almost a hundred years old. Before he died, they thought most wisely that it would be a great thing if the aged apostle set down his memories of the years when he had been with Jesus. But in the end they did far more than that. We can think of them sitting down and reliving the old days. One would say: “Do you remember how Jesus said … ?” And John would say: “Yes, and now we know that he meant…”

In other words this group was not only writing down what Jesus said; that would have been a mere feat of memory. They were writing down what Jesus meant; that was the guidance of the Holy Spirit. John had thought about every word that Jesus had said; and he had thought under the guidance of the Holy Spirit who was so real to him. W. M. Macgregor has a sermon entitled: “What Jesus becomes to a man who has known him long.” That is a perfect description of the Jesus of the Fourth Gospel. A. H. N. Green Armytage puts the thing perfectly in his book John who saw. Mark, he says, suits the missionary with his clear-cut account of the facts of Jesus’ life; Matthew suits the teacher with his systematic account of the teaching of Jesus; Luke suits the parish minister or priest with his wide sympathy and his picture of Jesus as the friend of all; but John is the gospel of the contemplative.

He goes on to speak of the apparent contrast between Mark and John. “The two gospels are in a sense the same gospel. Only, where Mark saw things plainly, bluntly, literally, John saw them subtly, profoundly, spiritually. We might say that John lit Mark’s pages by the lantern of a lifetime’s meditation.” Wordsworth defined poetry as “Emotion recollected in tranquility.” That is a perfect description of the Fourth Gospel. That is why John is unquestionably the greatest of all the gospels. Its aim is, not to give us what Jesus said like a newspaper report, but to give us what Jesus meant. In it the Risen Christ still speaks. John is not so much The Gospel according to St. John; it is rather The Gospel according to the Holy Spirit. It was not John of Ephesus who wrote the Fourth Gospel; it was the Holy Spirit who wrote it through John.

The Penman of the Gospel

We have one question still to ask. We can be quite sure that the mind and the memory behind the Fourth Gospel is that of John the apostle; but we have also seen that behind it is a witness who was the writer, in the sense that he was the actual penman. Can we find out who he was? We know from what the early church writers tell us that there were actually two Johns in Ephesus at the same time. There was John the apostle, but there was another John, who was known as John the elder.

Papias, who loved to collect all that he could find about the history of the New Testament and the story of Jesus, gives us some very interesting information. He was Bishop of Hierapolis, which is quite near Ephesus, and his dates are from about A.D. 70 to about A.D. 145. That is to say, he was actually a contemporary of John. He writes how he tried to find out “what Andrew said or what Peter said, or what was said by Philip, by Thomas, or by James, or by John, or by Matthew, or by any other of the disciples of the Lord; and what things Aristion and the elder John, the disciples of the Lord, say.” In Ephesus there was the apostle John, and the elder John; and the elder John was so well-loved a figure that he was actually known as The Elder. He clearly had a unique place in the church. Both Eusebius and Dionysius the Great tell us that even to their own days in Ephesus there were two famous tombs, the one of John the apostle, and the other of John the elder.

Now let us turn to the two little letters, Second John and Third John. The letters come from the same hand as the gospel, and how do they begin? The second letter begins: “The elder unto the elect lady and her children” (2 John 1:1 ). The third letter begins: “The elder unto the beloved Gaius” (3 John 1:1 ). Here we have our solution. The actual penman of the letters was John the elder; the mind and memory behind them was the aged John the apostle, the master whom John the elder always described as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.”

The Precious Gospel

The more we know about the Fourth Gospel the more precious it becomes. For seventy years John had thought of Jesus. Day by day the Holy Spirit had opened out to him the meaning of what Jesus said. So when John was near the century of life and his days were numbered, he and his friends sat down to remember. John the elder held the pen to write for his master, John the apostle; and the last of the apostles set down, not only what he had heard Jesus say, but also what he now knew Jesus had meant. He remembered how Jesus had said: “I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of Truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth” (John 16:12-13). There were many things which seventy years ago he had not understood; there were many things which in these seventy years the Spirit of Truth had revealed to him. These things John set down even as the eternal glory was dawning upon him. When we read this gospel let us remember that we are reading the gospel which of all the gospels is most the work of the Holy Spirit, speaking to us of the things which Jesus meant, speaking through the mind and memory of John the apostle and by the pen of John the elder. Behind this gospel is the whole church at Ephesus, the whole company of the saints, the last of the apostles, the Holy Spirit, the Risen Christ himself.

nb [Indirect Evidence]

an exhortation..as

an exhortation..as