from Science Set Free: 10 Paths to New Discovery; Prologue: Science, Religion and Power

[Published in UK as The Science Delusion]

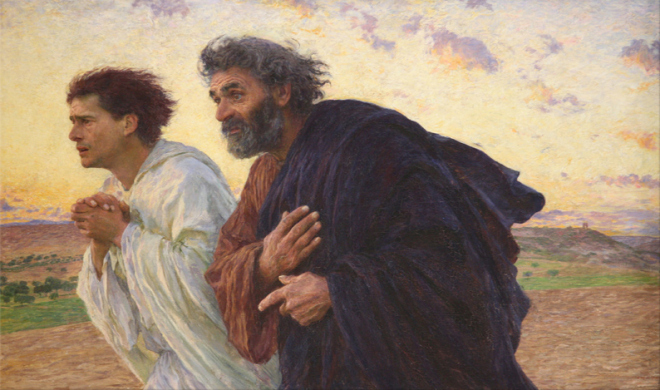

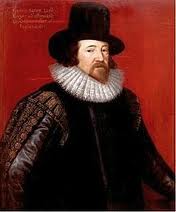

The scientific priesthood Francis Bacon (1561– 1626), a politician and lawyer who became Lord Chancellor of England, foresaw the power of organized science more than anyone else. To clear the way, he needed to show that there was nothing sinister about acquiring power over nature. When he was writing, there was a widespread fear of witchcraft and black magic, which he tried to counteract by claiming that knowledge of nature was God-given, not inspired by the devil. Science was a return to the innocence of the first man, Adam, in the Garden of Eden before the Fall.

Bacon argued that the first book of the Bible, Genesis, justified scientific knowledge. He equated man’s knowledge of nature with Adam’s naming of the animals. God “brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them, and what Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof” (Genesis 2: 19– 20). This was literally man’s knowledge, because Eve was not created until two verses later. Bacon argued that man’s technological mastery of nature was the recovery of a God-given power, rather than something new. He confidently assumed that people would use their new knowledge wisely and well: “Only let the human race recover that right over nature which belongs to it by divine bequest; the exercise thereof will be governed by sound reason and true religion.” [1]

The key to this new power over nature was organized institutional research. In New Atlantis (1624), Bacon described a technocratic Utopia in which a scientific priesthood made decisions for the good of the state as a whole. The Fellows of this scientific “Order or Society” wore long robes and were treated with a respect that their power and dignity required. The head of the order traveled in a rich chariot, under a radiant golden image of the sun. As he rode in procession, “he held up his bare hand, as he went, as blessing the people.”

The general purpose of this foundation was “the knowledge of causes and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible.” The Society was equipped with machinery and facilities for testing explosives and armaments, experimental furnaces, gardens for plant breeding, and dispensaries. [2]

This visionary scientific institution foreshadowed many features of institutional research, and was a direct inspiration for the founding of the Royal Society in London in 1660, and for many other national academies of science. But although the members of these academies were often held in high esteem, none achieved the grandeur and political power of Bacon’s imaginary prototypes. Their glory was continued even after their deaths in a gallery, like a Hall of Fame, where their images were preserved. “For upon every invention of value we erect a statue to the inventor, and give him a liberal and honourable reward.” [3]

In England in Bacon’s time (and still today) the Church of England was linked to the state as the established church. Bacon envisaged that the scientific priesthood would also be linked to the state through state patronage, forming a kind of established church of science. And here again he was prophetic. In nations both capitalist and Communist, the official academies of science remain the centers of power of the scientific establishment. There is no separation of science and state. Scientists play the role of an established priesthood, influencing government policies on the arts of warfare, industry, agriculture, medicine, education and research.

Bacon coined the ideal slogan for soliciting financial support from governments and investors: “Knowledge is power.”[4] But the success of scientists in eliciting funding from governments varied from country to country. The systematic state funding of science began much earlier in France and Germany than in Britain and the United States where, until the latter half of the nineteenth century, most research was privately funded or carried out by wealthy amateurs like Charles Darwin. [5]

In France, Louis Pasteur (1822– 95) was an influential proponent of science as a truth-finding religion, with laboratories like temples through which mankind would be elevated to its highest potential:

Take interest, I beseech you, in those sacred institutions which we designate under the expressive name of laboratories. Demand that they be multiplied and adorned; they are the temples of wealth and of the future. There it is that humanity grows, becomes stronger and better. [6]

By the beginning of the twentieth century, science was almost entirely institutionalized and professionalized, and after the Second World War expanded enormously under government patronage, as well as through corporate investment. [7] The highest level of funding is in the United States, where in 2008 the total expenditure on research and development was $ 398 billion, of which $ 104 billion came from the government. [8] But governments and corporations do not usually pay scientists to do research because they want innocent knowledge, like that of Adam before the Fall. Naming animals, as in classifying endangered species of beetles in tropical rain forests, is a low priority. Most funding is a response to Bacon’s persuasive slogan “knowledge is power.”

By the 1950s, when institutional science had reached an unprecedented level of power and prestige, the historian of science George Sarton approvingly described the situation in a way that sounds like the Roman Catholic Church before the Reformation:

Truth can be determined only by the judgment of experts. Everything is decided by very small groups of men, in fact, by single experts whose results are carefully checked, however, by a few others. The people have nothing to say but simply to accept the decisions handed out to them. Scientific activities are controlled by universities, academies and scientific societies, but such control is as far removed from popular control as it possibly could be. [9]

Bacon’s vision of a scientific priesthood has now been realized on a global scale. But his confidence that man’s power over nature would be guided by “sound reason and true religion” was misplaced.

Sheldrake, Rupert (2012-09-04). Science Set Free: 10 Paths to New Discovery (p. 13-16). Random House, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

[1] Collins, in Carr (ed.) (2007), pp. 50.

[2] Bacon (1951), pp. 290– 91.

[6] Dubos (1960), p. 146.

[8] National Science Board (2010), Chapter 4.

[9] Sarton (1955), p. 12.