Jesus again answered them in parables: “The Kingdom of Heaven is like the situation which arose when a man who was a king arranged a wedding for his son. He sent his servants to summon those who had been invited to the wedding, and they refused to come. He again sent other servants. ‘Tell those who have been invited,’ he said, ‘look you, I have my meal all prepared; my oxen and my specially fattened animals have been killed; and everything is ready. Come to the wedding.’ But they disregarded the invitation and went away, one to his estate, and another to his business. The rest seized the servants and treated them shamefully and killed them. The king was angry, and sent his armies, and destroyed those murderers, and set fire to their city. Then he said to his servants, ‘The wedding is ready. Those who have been invited did not deserve to come. Go, then, to the highways and invite to the wedding all you may find.’ So the servants went out to the roads, and collected all whom they found, both bad and good; and the wedding was supplied with guests.”

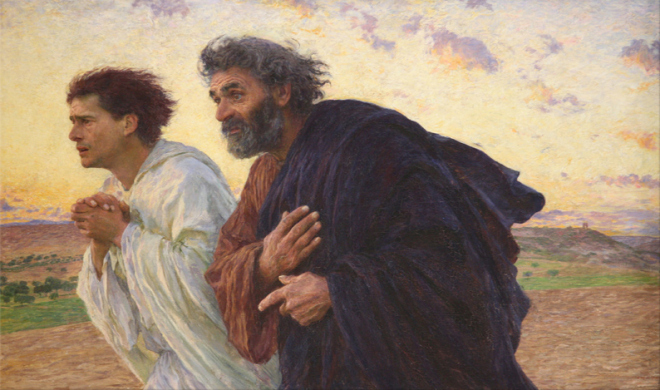

Parable of the Wedding Feast by Eugene Burnand

Matt 22:1-14 form not one parable, but two; and we will grasp their meaning far more easily and far more fully if we take them separately.

The events of the first of the two were completely in accordance with normal Jewish customs. When the invitations to a great feast, like a wedding feast, were sent out, the time was not stated; and when everything was ready the servants were sent out with a final summons to tell the guests to come. So, then, the king in this parable had long ago sent out his invitations; but it was not till everything was prepared that the final summons was issued—and insultingly refused. This parable has two meanings.

(i) It has a purely local meaning. Its local meaning was a driving home of what had already been, said in the Parable of the Wicked Husbandmen; once again it was an accusation of the Jews. The invited guests who when the time came refused to come, stand for the Jews. Ages ago they had been invited by God to be his chosen people; yet when God’s son came into the world, and they were invited to follow him they contemptuously refused. The result was that the invitation of God went out direct to the highways and the byways; and the people in the highways and the byways stand for the sinners and the Gentiles, who never expected an invitation into the Kingdom.

As the writer of the gospel saw it, the consequences of the refusal were terrible. There is one verse of the parable which is strangely out of place; and that because it is not part of the original parable as Jesus told it, but an interpretation by the writer of the gospel. That is Matt 22:7, which tells how the king sent his armies against those who refused the invitation, and burned their city.

Parable of the Wedding Feast by Eugene Burnand

This introduction of armies and the burning of the city seems at first sight completely out of place taken in connexion with invitations to a wedding feast. But Matthew was composing his gospel some time between A.D. 80 and 90. What had happened during the period between the actual life of Jesus and now? The answer is—the destruction of Jerusalem by the armies of Rome in A.D. 70. The Temple was sacked and burned and the city destroyed stone from stone, so that a plough was drawn across it. Complete disaster had come to those who refused to recognize the Son of God when he came.***

The Parable of the Wedding Feast by Eugene Burnand

The writer of the gospel adds as his comment the terrible things which did in fact happen to the nation which would not take the way of Christ. And it is indeed the simple historical fact that if the Jews had accepted the way of Christ, and had walked in love, in humility and in sacrifice they would never have been the rebellious, warring people who finally provoked the avenging wrath of Rome, when Rome could stand their political machinations no longer.

(ii) Equally this parable has much to say on a much wider scale.

(a) It reminds us that the invitation of God is to a feast as joyous as a wedding feast. His invitation is to joy. To think of Christianity as a gloomy giving up of everything which brings laughter and sunshine and happy fellowship is to mistake its whole nature. It is to joy that the Christian is invited; and it is joy he misses, if he refuses the invitation.

(b) It reminds us that the things which make men deaf to the invitation of Christ are not necessarily bad in themselves. One man went to his estate; the other to his business. They did not go off on a wild carousal or an immoral adventure. They went off on the [ task], in itself, excellent task of efficiently administering their business life. It is very easy for a man to be so busy with the things of time that he forgets the things of eternity, to be so preoccupied with the things which are seen that he forgets the things which are unseen, to hear so insistently the claims of the world that he cannot hear the soft invitation of the voice of Christ. The tragedy of life is that it is so often the second bests which shut out the bests, that it is things which are good in themselves which shut out the things that are supreme. A man can be so busy making a living that he fails to make a life; he can be so busy with the administration and the organization of life that he forgets life itself.

(c) It reminds us that the appeal of Christ is not so much to consider how we will be punished as it is to see what we will miss, if we do not take his way of things. Those who would not come were punished, but their real tragedy was that they lost the joy of the wedding feast. If we refuse the invitation of Christ, some day our greatest pain will lie, not in the things we suffer, but in the realization of the precious things we have missed.

(d) It reminds us that in the last analysis God’s invitation is the invitation of grace. Those who were gathered in from the highways and the byways had no claim on the king and they could never by any stretch of imagination have expected an invitation to the wedding feast, still less could they ever have deserved it. It came to them from nothing other than the wide-armed, open-hearted, generous hospitality of the king. It was grace which offered the invitation and grace which gathered men in.

The king came in to see those who were sitting at table, and he saw there a man who was not wearing a wedding garment. “Friend,” he said to him, “how did you come here with no wedding garment?” The man was struck silent. Then the king said to the attendants, “Bind him hands and feet, and throw him out into the outer darkness. There shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth there. For many are called, but few are chosen.”

This is a second parable, but it is also a very close continuation and amplification of the previous one. It is the story of a guest who appeared at a royal wedding feast without a wedding garment.

One of the great interests of this parable is that in it we see Jesus taking a story which was already familiar to his hearers and using it in his own way. The Rabbis had two stories which involved kings and garments. The first told of a king who invited his guests to a feast, without telling them the exact date and time; but he did tell them that they must wash, and anoint, and clothe themselves that they might be ready when the summons came. The wise prepared themselves at once, and took their places waiting at the palace door, for they believed that in a palace a feast could be prepared so quickly that there would be no long warning. The foolish believed that it would take a long time to make the necessary preparations and that they would have plenty of time. So they went, the mason to his lime, the potter to his clay, the smith to his furnace, the fuller to his bleaching-ground, and went on with their work. Then, suddenly, the summons to the feast came without any warning. The wise were ready to sit down, and the king rejoiced over them, and they ate and drank. But those who had not arrayed themselves in their wedding garments had to stand outside, sad and hungry, and look on at the joy that they had lost. That rabbinic parable tells of the duty of preparedness for the summons of God, and the garments stand for the preparation that must be made.

One of the great interests of this parable is that in it we see Jesus taking a story which was already familiar to his hearers and using it in his own way. The Rabbis had two stories which involved kings and garments. The first told of a king who invited his guests to a feast, without telling them the exact date and time; but he did tell them that they must wash, and anoint, and clothe themselves that they might be ready when the summons came. The wise prepared themselves at once, and took their places waiting at the palace door, for they believed that in a palace a feast could be prepared so quickly that there would be no long warning. The foolish believed that it would take a long time to make the necessary preparations and that they would have plenty of time. So they went, the mason to his lime, the potter to his clay, the smith to his furnace, the fuller to his bleaching-ground, and went on with their work. Then, suddenly, the summons to the feast came without any warning. The wise were ready to sit down, and the king rejoiced over them, and they ate and drank. But those who had not arrayed themselves in their wedding garments had to stand outside, sad and hungry, and look on at the joy that they had lost. That rabbinic parable tells of the duty of preparedness for the summons of God, and the garments stand for the preparation that must be made.

The second rabbinic parable told how a king entrusted to his servants royal robes. Those who were wise took the robes, and carefully stored them away, and kept them in all their pristine loveliness. Those who were foolish wore the robes to their work, and soiled and stained them. The day came when the king demanded the robes back. The wise handed them back fresh and clean; so the king laid up the robes in his treasury and bade them go in peace. The foolish handed them back stained and soiled. The king commanded that the robes should be given to the fuller to cleanse, and that the foolish servants should be cast into prison. This parable teaches that a man must hand back his soul to God in all its original purity; but that the man who has nothing but a stained soul to render back stands condemned.

No doubt Jesus had these two parables in mind when he told his own story. What, then, was he seeking to teach? This parable also contains both a local and a universal lesson.

Parable of the Wedding Feast by Eugene Burnand

(i) The local lesson is this. Jesus has just said that the king, to supply his feast with guests, sent his messengers out into the highways and byways to gather all men in. That was the parable of the open door. It told how the Gentiles and the sinners would be gathered in. This parable strikes the necessary balance. It is true that the door is open to all men, but when they come they must bring a life which seeks to fit the love which has been given to them. Grace is not only a gift; it is a grave responsibility. A man cannot go on living the life he lived before he met Jesus Christ. He must be clothed in a new purity and a new holiness and a new goodness. The door is open, but the door is not open for the sinner to come and remain a sinner, but for the sinner to come and become a saint.

(ii) This is the permanent lesson. The way in which a man comes to anything demonstrates the spirit in which he comes. If we go to visit in a friend’s house, we do not go in the clothes we wear in the shipyard or the garden. We know very well that it is not the clothes which matter to the friend. It is not that we want to put on a show. It is simply a matter of respect that we should present ourselves in our friend’s house as neatly as we can. The fact that we prepare ourselves to go there is the way in which we outwardly show our affection and our esteem for our friend. So it is with God’s house. This parable has nothing to do with the clothes in which we go to church; it has everything to do with the spirit in which we go to God’s house. It is profoundly true that church-going must never be a fashion parade. But there are garments of the mind and of the heart and of the soul—the garment of expectation, the garment of humble penitence, the garment of faith, the garment of reverence—and these are the garments without which we ought not to approach God. Too often we go to God’s house with no preparation at all; if every man and woman in our congregations came to church prepared to worship, after a little prayer, a little thought, and a little self-examination, then worship would be worship indeed—the worship in which and through which things happen in men’s souls and in the life of the Church and in the affairs of the world.

Parable of the Wedding Feast by Eugene Burnand

***[There is a good argument for an earlier composition of Matthew than Barclay’s 80-90 AD, which makes Jesus prophetic in this parable as Matthew 24 would be as well if this Gospel was penned prior to AD 70 cf., R.C. Sproul, The Last Days of Jesus according to Jesus]

Gospel of Matthew Vol II; by William Barclay; Barclay’s Daily Study Bible (NT).