Tag / Bible

The Original Women’s Liberation Movement – YouTube

Reasons To Believe : Genesis Creation Days: An Interview with Dr. T. David Gordon

Hell–from The Problem of Pain, by C.S. Lewis

I am not going to try to prove the doctrine tolerable. Let us make no mistake; it is not tolerable. But I think the doctrine can be shown to be moral, by a critique of the objections ordinarily made, or felt, against it.

First, there is an objection, in many minds, to the idea of retributive punishment as such. This has been partly dealt with in a previous chapter. It was there maintained that all punishment became unjust if the ideas of ill-desert and retribution were removed from it; and a core of righteousness was discovered within the vindictive passion its self, in the demand that the evil man must not be left perfectly satisfied with his own evil, that it must be made to appear to him what it rightly appears to others—evil. I said that Pain plants the flag of truth within a rebel fortress. We were then discussing pain which might still lead to repentance. How if it does not—if no further conquest than the planting of the flag ever takes place?

Let us try to be honest with ourselves. Picture to yourself a man who has risen to wealth or power by a continued course of treachery and cruelty, by exploiting for purely selfish ends the noble motions of his victims, laughing the while at their simplicity; who, having thus attained success, uses it for the gratification of lust and hatred and finally parts with the last rag of honour among thieves by betraying his own accomplices and jeering at their last moments of bewildered disillusionment. Suppose, further, that he does all this, not (as we like to imagine) tormented by remorse or even misgiving, but eating like a schoolboy and sleeping like a healthy infant—a jolly, ruddy-cheeked man, without a care in the world, unshakably confident to the very end that he alone has found the answer to the riddle of life, that God and man are fools whom he has got the better of, that his way of life is utterly successful, satisfactory, unassailable. We must be careful at this point. The least indulgence of the passion for revenge is very deadly sin. Christian charity counsels us to make every effort for the conversion of such a man: to prefer his conversion, at the peril of our own lives, perhaps of our own souls, to his punishment; to prefer it infinitely.

But that is not the question. Supposing he will not be converted, what destiny in the eternal world can you regard as proper for him? Can you really desire that such a man, remaining what he is (and he must be able to do that if he has free will) should be confirmed forever in his present happiness—should continue, for all eternity, to be perfectly convinced that the laugh is on his side? And if you cannot regard this as tolerable, is it only your wickedness—only spite—that prevents you from doing so? Or do you find that conflict between Justice and Mercy, which has sometimes seemed to you such an outmoded piece of theology, now actually at work in your own mind, and feeling very much as if it came to you from above, not from below? You are moved not by a desire for the wretched creature’s pain as such, but by a truly ethical demand that, soon or late, the right should be asserted, the flag planted in this horribly rebellious soul, even if no fuller and better conquest is to follow. In a sense, it is better for the creature its self, even if it never becomes good, that it should know its self a failure, a mistake. Even mercy can hardly wish to such a man his eternal, contented continuance in such ghastly illusion. Thomas Aquinas said of suffering, as Aristotle had said of shame, that it was a thing not good in its self; but a thing which might have a certain goodness in particular circumstances. That is to say, if evil is present, pain at recognition of the evil, being a kind of knowledge, is relatively good; for the alternative is that the soul should be ignorant of the evil, or ignorant that the evil is contrary to its nature, ‘either of which’, says the philosopher, ‘is manifestly bad’.* And I think, though we tremble, we agree.

The demand that God should forgive such a man while he remains what he is, is based on a confusion between condoning and forgiving. To condone an evil is simply to ignore it, to treat it as if it were good. But forgiveness needs to be accepted as well as offered if it is to be complete: and a man who admits no guilt can accept no forgiveness.

I have begun with the conception of Hell as a positive retributive punishment inflicted by God because that is the form in which the doctrine is most repellent, and I wished to tackle the strongest objection. But, of course, though Our Lord often speaks of Hell as a sentence inflicted by a tribunal, He also says elsewhere that the judgement consists in the very fact that men prefer darkness to light, and that not He, but His ‘word’, judges men** We are therefore at liberty—since the two conceptions, in the long run, mean the same thing—to think of this bad man’s perdition not as a sentence imposed on him but as the mere fact of being what he is. The characteristic of lost souls is ‘their rejection of everything that is not simply themselves’.*** Our imaginary egoist has tried to turn everything he meets into a province or appendage of the self. The taste for the other, that is, the very capacity for enjoying good, is quenched in him except in so far as his body still draws him into some rudimentary contact with an outer world. Death removes this last contact. He has his wish—to lie wholly in the self and to make the best of what he finds there. And what he finds there is Hell.

1 Summa Theol, I, IIae, Q. xxxix, Art. 1.

** John 3:19; 12:48.

*** See von Hügel, Essays and Addresses, 1st series, What do we mean by Heaven and Hell?

Lewis, C. S. (2009-05-28). The Problem of Pain (p.123- 125). Harper Collins, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

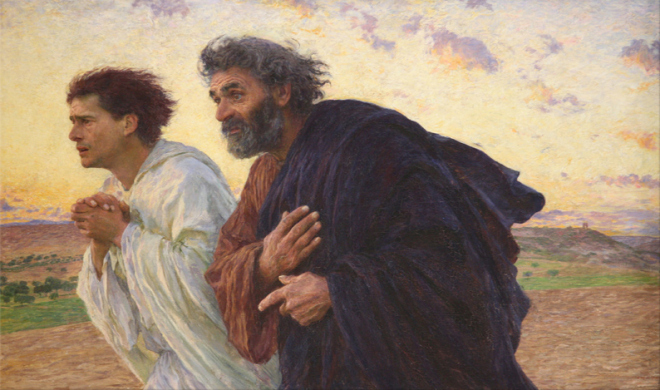

Why did the Apostle John refer to himself as, “the disciple whom Jesus loved,”?

From INTRODUCTION TO THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SAINT JOHN Vol.I

By William Barclay

The Beloved Disciple

… All our information about John comes from the first three gospels. It is the astonishing fact that the Fourth Gospel never mentions the apostle John from beginning to end. But it does mention two other people.

First, it speaks of the disciple whom Jesus loved. There are four mentions of him. He was leaning on Jesus’ breast at the Last Supper (John 13:23-25); it is into his care that Jesus committed Mary as he died upon his Cross (John 19:25-27); it was Peter and he whom Mary Magdalene met on her return from the empty tomb on the first Easter morning (John 20:2); he was present at the last resurrection appearance of Jesus by the lake-side (John 21:20).

Second, the Fourth Gospel has a kind of character whom we might call the witness. As the Fourth Gospel tells of the spear thrust into the side of Jesus and the issue of the water and the blood, there comes the comment: “He who saw it has borne witness–his testimony is true, and he knows that he tells the truth–that you also may believe” (John 19:35). At the end of the gospel comes the statement that it was the beloved disciple who testified of these things “and we know that his testimony is true” (John 21:24).

Here we are faced with rather a strange thing. In the Fourth Gospel John is never mentioned, but the beloved disciple is and in addition there is a witness of some kind to the whole story. It has never really been doubted in tradition that the beloved disciple is John. A few have tried to identify him with Lazarus, for Jesus is said to have loved Lazarus (John 11:3-5), or with the Rich Young Ruler, of whom it is said that Jesus, looking on him, loved him (Mark 10:21). But although the gospel never says so in so many words, tradition has always identified the beloved disciple with John, and there is no real need to doubt the identification.

But a very real point arises–suppose John himself actually did the writing of the gospel, would he really be likely to speak of himself as the disciple whom Jesus loved? Would he really be likely to pick himself out like this, and, as it were, to say: “I was his favourite; he loved me best of all”? It is surely very unlikely that John would confer such a title on himself. If it was conferred by others, it is a lovely title; if it was conferred by himself, it comes perilously near to an almost incredible self-conceit.

Is there any way then that the gospel can be John’s own eye-witness story, and yet at the same time have been actually written down by someone else?

The Production of the Church

In our search for the truth we begin by noting one of the outstanding and unique features of the Fourth Gospel. The most remarkable thing about it is the long speeches of Jesus. Often they are whole chapters long, and are entirely unlike the way in which Jesus is portrayed as speaking in the other three gospels. The Fourth Gospel, as we have seen, was written about the year A.D. 100, that is, about seventy years after the crucifixion. Is it possible after these seventy years to look on these speeches as word for word reports of what Jesus said? Or can we explain them in some way that is perhaps even greater than that? We must begin by holding in our minds the fact of the speeches and the question which they inevitably raise.

And we have something to add to that. It so happens that in the writings of the early church we have a whole series of accounts of the way in which the Fourth Gospel came to be written. The earliest is that of Irenaeus who was bishop of Lyons about A.D. 177; and Irenaeus was himself a pupil of Polycarp, who in turn had actually been a pupil of John. There is therefore a direct link between Irenaeus and John. Irenaeus writes:

“John, the disciple of the Lord, who also leant upon his breast,

himself also published the gospel in Ephesus, when he was living

in Asia.”

The suggestive thing there is that Irenaeus does not merely say that John wrote the gospel; he says that John published (exedoke) it in Ephesus. The word that Irenaeus uses makes it sound, not like the private publication of some personal memoir, but like the public issue of some almost official document.

The next account is that of Clement who was head of the great school of Alexandria about A.D. 230. He writes:

“Last of all, John perceiving that the bodily facts had been made

plain in the gospel, being urged by his friends, composed a

spiritual gospel.”

The important thing here is the phrase being urged by his friends. It begins to become clear that the Fourth Gospel is far more than one man’s personal production and that there is a group, a community, a church behind it. On the same lines, a tenth-century manuscript called the Codex Toletanus, which prefaces the New Testament books with short descriptions, prefaces the Fourth Gospel thus:

“The apostle John, whom the Lord Jesus loved most, last of all

wrote this gospel, at the request of the bishops of Asia, against

Cerinthus and other heretics.”

Again we have the idea that behind the Fourth Gospel there is the authority of a group and of a church.

We now turn to a very important document, known as the Muratorian Canon. It is so called after a scholar Muratori who discovered it. It is the first list of New Testament books which the church ever issued and was compiled in Rome about A.D. 170. Not only does it list the New Testament books, it also gives short accounts of the origin and nature and contents of each of them. Its account of the way in which the Fourth Gospel came to be written is extremely important and illuminating.

“At the request of his fellow-disciples and of his bishops, John,

one of the disciples, said: ‘Fast with me for three days from

this time and whatsoever shall be revealed to each of us, whether it be favourable to my writing or not, let us relate it to one another.’ On the same night it was revealed to Andrew that John should relate all things, aided by the revision of all.”

We cannot accept all that statement, because it is not possible that Andrew, the apostle, was in Ephesus in A.D. 100; but the point is that it is stated as clearly as possible that, while the authority and the mind and the memory behind the Fourth Gospel are that of John, it is clearly and definitely the product, not of one man, but of a group and a community.

Now we can see something of what happened. About the year A.D. 100 there was a group of men in Ephesus whose leader was John. They revered him as a saint and they loved him as a father. He must have been almost a hundred years old. Before he died, they thought most wisely that it would be a great thing if the aged apostle set down his memories of the years when he had been with Jesus. But in the end they did far more than that. We can think of them sitting down and reliving the old days. One would say: “Do you remember how Jesus said … ?” And John would say: “Yes, and now we know that he meant…”

In other words this group was not only writing down what Jesus said; that would have been a mere feat of memory. They were writing down what Jesus meant; that was the guidance of the Holy Spirit. John had thought about every word that Jesus had said; and he had thought under the guidance of the Holy Spirit who was so real to him. W. M. Macgregor has a sermon entitled: “What Jesus becomes to a man who has known him long.” That is a perfect description of the Jesus of the Fourth Gospel. A. H. N. Green Armytage puts the thing perfectly in his book John who saw. Mark, he says, suits the missionary with his clear-cut account of the facts of Jesus’ life; Matthew suits the teacher with his systematic account of the teaching of Jesus; Luke suits the parish minister or priest with his wide sympathy and his picture of Jesus as the friend of all; but John is the gospel of the contemplative.

He goes on to speak of the apparent contrast between Mark and John. “The two gospels are in a sense the same gospel. Only, where Mark saw things plainly, bluntly, literally, John saw them subtly, profoundly, spiritually. We might say that John lit Mark’s pages by the lantern of a lifetime’s meditation.” Wordsworth defined poetry as “Emotion recollected in tranquility.” That is a perfect description of the Fourth Gospel. That is why John is unquestionably the greatest of all the gospels. Its aim is, not to give us what Jesus said like a newspaper report, but to give us what Jesus meant. In it the Risen Christ still speaks. John is not so much The Gospel according to St. John; it is rather The Gospel according to the Holy Spirit. It was not John of Ephesus who wrote the Fourth Gospel; it was the Holy Spirit who wrote it through John.

The Penman of the Gospel

We have one question still to ask. We can be quite sure that the mind and the memory behind the Fourth Gospel is that of John the apostle; but we have also seen that behind it is a witness who was the writer, in the sense that he was the actual penman. Can we find out who he was? We know from what the early church writers tell us that there were actually two Johns in Ephesus at the same time. There was John the apostle, but there was another John, who was known as John the elder.

Papias, who loved to collect all that he could find about the history of the New Testament and the story of Jesus, gives us some very interesting information. He was Bishop of Hierapolis, which is quite near Ephesus, and his dates are from about A.D. 70 to about A.D. 145. That is to say, he was actually a contemporary of John. He writes how he tried to find out “what Andrew said or what Peter said, or what was said by Philip, by Thomas, or by James, or by John, or by Matthew, or by any other of the disciples of the Lord; and what things Aristion and the elder John, the disciples of the Lord, say.” In Ephesus there was the apostle John, and the elder John; and the elder John was so well-loved a figure that he was actually known as The Elder. He clearly had a unique place in the church. Both Eusebius and Dionysius the Great tell us that even to their own days in Ephesus there were two famous tombs, the one of John the apostle, and the other of John the elder.

Now let us turn to the two little letters, Second John and Third John. The letters come from the same hand as the gospel, and how do they begin? The second letter begins: “The elder unto the elect lady and her children” (2 John 1:1 ). The third letter begins: “The elder unto the beloved Gaius” (3 John 1:1 ). Here we have our solution. The actual penman of the letters was John the elder; the mind and memory behind them was the aged John the apostle, the master whom John the elder always described as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.”

The Precious Gospel

The more we know about the Fourth Gospel the more precious it becomes. For seventy years John had thought of Jesus. Day by day the Holy Spirit had opened out to him the meaning of what Jesus said. So when John was near the century of life and his days were numbered, he and his friends sat down to remember. John the elder held the pen to write for his master, John the apostle; and the last of the apostles set down, not only what he had heard Jesus say, but also what he now knew Jesus had meant. He remembered how Jesus had said: “I have yet many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of Truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth” (John 16:12-13). There were many things which seventy years ago he had not understood; there were many things which in these seventy years the Spirit of Truth had revealed to him. These things John set down even as the eternal glory was dawning upon him. When we read this gospel let us remember that we are reading the gospel which of all the gospels is most the work of the Holy Spirit, speaking to us of the things which Jesus meant, speaking through the mind and memory of John the apostle and by the pen of John the elder. Behind this gospel is the whole church at Ephesus, the whole company of the saints, the last of the apostles, the Holy Spirit, the Risen Christ himself.

from The Problem of Pain, by C.S. Lewis

From the moment a creature becomes aware of God as God and of it’self as self, the terrible alternative of choosing God or self for the centre is opened to it. This sin is committed daily by young children and ignorant peasants as well as by sophisticated persons, by solitaries no less than by those who live in society: it is the fall in every individual life, and in each day of each individual life, the basic sin behind all particular sins: at this very moment you and I are either committing it, or about to

commit it, or repenting it. We try, when we wake, to lay the new day at God’s feet; before we have finished shaving, it becomes our day and God’s share in it is felt as a tribute which we must pay out of ‘our own’ pocket, a deduction from the time which ought, we feel, to be ‘our own’.

Lewis, C. S. (2009-05-28). The Problem of Pain (p. 70). Harper Collins, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

Believing

Our love

Our love is all of God’s money

Everyone is a burning sun

-Jeff Tweedy

Belief is the locked up tangible thing,

of law that the dust can be blown off of,

taken from a bookshelf, objectified, crucified

pointed at, solid repository of ideological contusions,

Gnostic misdemeanors, white lies & black ones of unreality

no different from the adulterous

first degree murder of guilty abrasions on your soul & woeful

finger-pointing wrong in legalistic right…

“Liberals and fundamentalists are both humanists,” said the old preacher grinning as he cleaned the carburetor of his Buick with Joy from a yellow plastic bottle & a tooth brush

“One believes there is a better day a coming, all with a strong right arm of correct politics, & culture change.

“The other believes there is a better day a coming, if you do everything the Bible say; both have made Man’s action the operative & left out God as the agent of change. ” Then after putting the air cleaner back together, he laughed and said, “Isn’t it interesting that moralism gets us only so far!”

Rolling up through time & space containerized in

This bone-bag existence of drunken pleasure & pain

& psychedelic sin

& death…

Thankfully,

Believing is..

alive

the BE Living,

the BE loving

Believing is..

Holy Spirit..

Who is…

fluid active running down the river & the red fish

in the river & the same thing and is this River of Life flowing from us..

living water of life on this planet flowing from us somehow..

that gets us to the other side

& brings us back

A-gain,

A resurrection

A dilation of time, in this space–from another one.

so the bone bag has some kin

w/ the reddening sky,

mist on the mountain

bird song, moon rising

star twinkle ’round Orion’s belt

& sun setting over placid ocean

& laughter of a four year old son,

keeper of His kingdom

the Life is..

the forgiving cry of the first born Son

Who is…

the Truth, blessed Yeshua

the Way, to get though this life w/joy,

perseverance, love &

everlasting knowledge..

“Our Father in heaven..”

Who is…

& because His name is..

so Hallowed

this is…

within us &

all so, “On earth as it is in Heaven.”

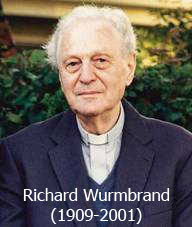

Richard Wurmbrand, “Preparing for the Underground Church”

“God is the Truth. The Bible is the truth about the Truth. Theology is the truth about the truth about the Truth. A good sermon is the truth about the truth, about the truth, about the Truth. It is not the Truth. The Truth is God alone. Around this Truth there is a scaffolding of words, of theologies, and of exposition. None of these is of any help in times of suffering. It is only the Truth Himself Who is of help, and we have to penetrate through sermons, through theological books, through everything which is ‘words’ and be bound up with the reality of God himself.

I have told in the West how Christians were tied to crosses for four days and four nights. The crosses were put on the floor and other prisoners were tortured and made to fulfill their bodily necessities upon the faces and bodies of the crucified ones. I have since been asked: “Which bible verse helped and strengthened you in those circumstances?” My answer is: “NO Bible verse was of any help.” It is sheer cant and religious hypocrisy to say, “This Bible verse strengthens me, or that Bible verse helps me.” Bible verses alone are not meant to help. We knew Psalm 23.. “The Lord is my Shepherd; I shall not want…though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…”

When you pass through suffering you realize that it was never meant by God that Psalm 23 should strengthen you. It is the Lord who can strengthen you, not the Psalm which speaks of Him so doing. It is not enough to have the Psalm. You must have the One about whom the Psalm speaks. We also knew the verse: “My Grace is sufficient for thee.” But the verse is not sufficient. It is the Grace, which is sufficient, and not the verse.

Pastors and zealous witnesses who are handling the Word as a calling from God are in danger of giving Holy words more value than they really have. Holy words are only the means to arrive at the reality expressed by them. If you are united with the Reality, the Lord Almighty, evil loses its power over you; it cannot break the Lord Almighty. If you only have the words of the Lord almighty you can be very easily broken.” Richard Wurmbrand, “Preparing for the Underground Church”