A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF BIOLOGY

When things are going smoothly in our lives most of us tend to think that the society we live in is “natural,” and that our ideas about the world are self-evidently true. It’s hard to imagine how other people in other times and places lived as they did or why they believed the things they did. During periods of upheaval, however, when apparently solid verities are questioned, it can seem as if nothing in the world makes sense. During those times history can remind us that the search for reliable knowledge is a long, difficult process that has not yet reached an end. In order to develop a perspective from which we can view the idea of Darwinian evolution, over the next few pages I will very briefly outline the history of biology. In a way, this history has been a chain of black boxes; as one is opened, another is revealed. Black box is a whimsical term for a device that does something, but whose inner workings are mysterious—sometimes because the workings can’t be seen, and sometimes because they just aren’t comprehensible. Computers are a good example of a black box. Most of us use these marvelous machines without the vaguest idea of how they work, processing words or plotting graphs or playing games in contented ignorance of what is going on underneath the outer case. Even if we were to remove the cover, though, few of us could make heads or tails of the jumble of pieces inside. There is no simple, observable connection between the parts of the computer and the things that it does. Imagine that a computer with a long-lasting battery was transported back in time a thousand years to King Arthur’s court. How would people of that era react to a computer in action? Most would be in awe, but with luck someone might want to understand the thing. Someone might notice that letters appeared on the screen as he or she touched the keys. Some combinations of letters—corresponding to computer commands—might make the screen change; after a while, many commands would be figured out. Our medieval Englishmen might believe they had unlocked the secrets of the computer. But eventually somebody would remove the cover and gaze on the computer’s inner workings. Suddenly the theory of “how a computer works” would be revealed as profoundly naive. The black box that had been slowly decoded would have exposed another black box. In ancient times allof biology was a black box, because no one understood on even the broadest level how living things worked. The ancients who gaped at a plant or animal and wondered just how the thing worked were in the presence of unfathomable technology. They were truly in the dark. The earliest biological investigations began in the only way they could—with the naked eye.2 A number of books from about 400 B.C. (attributed to Hippocrates, the “father of medicine”) describe the symptoms of some common diseases and attribute sickness to diet and other physical causes, rather than to the work of the gods. Although the writings were a beginning, the ancients were still lost when it came to the composition of living things. They believed that all matter was made up of four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Living bodies were thought to be made of four “humors”—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm—and all disease supposedly arose from an excess of one of the humors. The greatest biologist of the Greeks was also their greatest philosopher, Aristotle. Born when Hippocrates was still alive, Aristotle realized (unlike almost everyone before him) that knowledge of nature requires systematic observation. Through careful examination he recognized an astounding amount of order within the living world, a crucial first step. Aristotle grouped animals into two general categories—those with blood, and those without—that correspond closely to the modern classifications of vertebrate and invertebrate. Within the vertebrates he recognized the categories of mammals, birds, and fish. He put most amphibians and reptiles in a single group, and snakes in a separate class. Even though his observations were unaided by instruments, much of Aristotle’s reasoning remains sound despite the knowledge gained in the thousands of years since he died. Only a few significant biological investigators lived during the millennium following Aristotle. One of them was Galen, a second-century A.D. physician in Rome. Galen’s work shows that careful observation of the outside and (with dissection) the inside of plants and animals, although necessary, is not sufficient to comprehend biology. For example, Galen tried to understand the function of animal organs. Although he knew that the heart pumped blood, he could not tell just from looking that the blood circulated and returned to the heart. Galen mistakenly thought that blood was pumped out to “irrigate” the tissues, and that new blood was made continuously to resupply the heart. His idea was taught for nearly fifteen hundred years. It was not until the seventeenth century that an Englishman, William Harvey, introduced the theory that blood flows continuously in one direction, making a complete circuit and returning to the heart. Harvey calculated that if the heart pumps out just two ounces of blood per beat, at 72 beats per minute, in one hour it would have pumped 540 pounds of blood—triple the weight of a man! Since making that much blood in so short a time is clearly impossible, the blood had to be reused. Harvey’s logical reasoning (aided by the still-new Arabic numerals, which made calculating easy) in support of an unobservable activity was unprecedented; it set the stage for modern biological thought. In the Middle Ages the pace of scientific investigation quickened. The example set by Aristotle had been followed by increasing numbers of naturalists. Many plants were described by the early botanists Brunfels, Bock, Fuchs, and Valerius Cordus. Scientific illustration developed as Rondelet drew animal life in detail. The encyclopedists, such as Conrad Gesner, published large volumes summarizing all of biological knowledge. Linnaeus greatly extended Aristotle’s work of classification, inventing the categories of class, order, genus, and species. Studies of comparative biology showed many similarities between diverse branches of life, and the idea of common descent began to be discussed. Biology advanced rapidly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as scientists combined Aristotle’s and Harvey’s examples of attentive observation and clever reasoning. Yet even the strictest attention and cleverest reasoning will take you only so far if important parts of a system aren’t visible. Although the human eye can resolve objects as small as one-tenth of a millimeter, a lot of the action in life occurs on a micro level, a Lilliputian scale. So biology reached a plateau: One black box, the gross structure of organisms, was opened only to reveal the black box of the finer levels of life. In order to proceed further biology needed a series of technological breakthroughs. The first was the microscope.

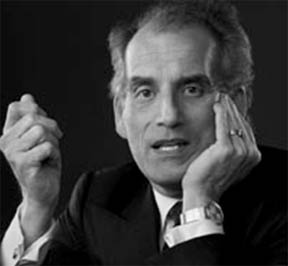

Behe, Michael J. (2001-04-04). Darwin’s Black Box (Kindle Locations 142-194). Simon & Schuster, Inc.. Kindle Edition.