C.S. Lewis

And being very tired and having nothing inside him he felt so sorry for himself that the tears rolled down his cheeks.

What put a stop to all this was a sudden fright. Shasta discovered that someone or somebody was walking beside him, it was pitch dark and he could see nothing. And the Thing (or Person) was so quietly beside him he could hardly hear any footfalls. What he could hear was breathing. His invisible companion seemed to breathe on a very large scale and Shasta got the impression that it was a very large creature. And he had come to notice this breathing so gradually that he had really no idea how long it had been there, It was a horrible shock.

It darted into his mind that he heard long ago that there were Giants in these northern countries. He bit his lip in terror. But now that he really had something to cry about, he stopped crying.

The Thing (unless it was a Person) went on beside him so very quietly that Shasta began to hope he had only imagined it. But just as he was becoming quite sure of it, there suddenly came a deep, rich sigh out of the darkness beside him. That couldn’t be imagination! Anyway, he had felt the hot breath of the sigh on his chilly left hand.

If the horse had been any good—or he had known how to get any good out of the horse— he would have risked everything on a break away and a wild gallop. But he knew he couldn’t make that horse gallop. So he went on at a walking pace and the unseen companion walked and breathed beside him. At last he could bear it no longer.

“Who are you?” he said, scarcely above a whisper.

“One who has waited long for you to speak,” said the Thing. Its voice was not loud, but very large and deep.

“Are you —a giant?” asked Shasta.

“You might call me a giant,” said the Large Voice. “But I am not like any creatures you call Giants.”

“I can’t see you at all,” said Shasta, after staring very hard, then (for an even more terrible idea had come into his head) he said, almost in a scream, “You’re not something dead, are you? Oh, please—do go away, what harm have I ever done you? Oh, I am the unluckiest person in the whole world!”

Once more he felt the warm breath of the Thing on his hand and face. “There,” it said, “that is not the breath of a ghost, tell me you sorrows.”

Shasta was a little reassured by the breath: so he told how he had never known his real father or mother and had been brought up sternly by the fisherman. And then he told the story of his escape and how they were chased by lions and forced to swim for their lives; and of all the dangers in Tashban and about his night among the tombs and how the beasts howled at him out of the desert. And he told about the heat and the thirst of their desert journey. And he told about how they were almost at their goal when another lion chased them and wounded Aravis. And also, how very long it was since he’d had anything to eat.

“I do not call you unfortunate,” said the Large Voice.

“Don’t you think it was bad luck to meet so may lions?” said Shasta.

“There was only one Lion, Said the Voice.

“What on earth do you mean? I’ve just told you there were at least two the first night, and..”

“There was only one: but he was swift of foot.”

“How do you know?”

“I was the lion.” And as Shasta gaped with open mouth and said nothing, the voice continued, “I was the lion who forced you to join with Aravis. I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead, I was the Lion who drove the jackals from you while you slept. I was the lion who gave the horse the new strength of fear for the last mile so that you should reach King Lune in time, and I was the lion you do not remember who pushed the boat in which you lay, a child near death, so that it came to shore where a man sat, wakeful at midnight, to receive you.”

“Then it was you who wounded Aravis?”

“It was I.”

“But what for?” said Shasta.

“Child,” said the Voice “I am telling you, your story, not theirs. I tell no one any story but his own.”

“Who are you?” said Shasta.

“Myself,” said the Voice, very deep and low so that the earth shook: and again,” Myself,” loud and clear and gay: and then the third time “Myself,” whispered so softly you could hardly hear it, and yet it seemed to come from all around you as if the leaves rustled with it.

Shasta was no longer afraid that the Voice belonged to something that would eat him, nor that it was the voice of a ghost, but a new and different sort of trembling came over him, yet he felt glad too.

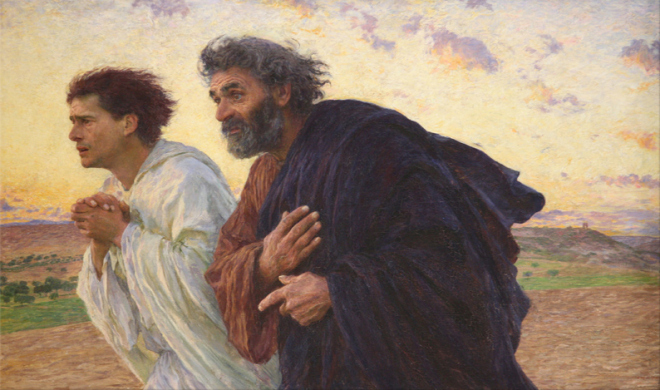

The mist was turning from black to gray, and from gray to white. This must have begun to happen some time ago, but while he had been talking to the Thing he had not been noticing anything else. Now, the whiteness around him became a shining whiteness; his eyes began to blink, somewhere ahead he could hear birds singing. He knew the night was over a last. He could see the mane and ears and head of his horse quite easily now. A golden light fell on them from the left. He thought it was the sun.

He turned and saw, pacing beside him, taller than the horse, a Lion. The horse did not seem to be afraid of it or else could not see it. It was from the Lion that the light came. No one ever saw anything more terrible or beautiful. Luckily Shasta had lived all his life too far south in Calormen to have heard the tales that were whispered in Tashbaan about the dreadful Narnian demon that appeared in the form of a lion. And of course he knew none of the true stores about Aslan, the great Lion, the son of the Emperor-over-the Sea, the King above all High Kings in Narnia. But after one glance at the Lion’s face, he slipped out of the saddle and fell at its feet. He couldn’t say anything but then he didn’t want to say anything, and he knew he couldn’t say anything.

The Horse and His Boy by C.S. Lewis